Composers and Choreographers

STANLEY ROSEMAN

Drawings

Drawings

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

"The rehearsal halls and the wings of the stage of the Paris Opéra were my studio, and many of the greatest dancers today were the subjects of my drawings.

Even with the familiarity of repeated performances,

I could not contain the excitement I felt each time I resumed my work.

I was inspired by the music and the dance to draw.''

Even with the familiarity of repeated performances,

I could not contain the excitement I felt each time I resumed my work.

I was inspired by the music and the dance to draw.''

- Stanley Roseman

Stanley Roseman drawing the dance from the wings of the stage of the Paris Opéra

Music is a stimulating force for the choreographer and the dancer and was also for Roseman drawing dancers in Romantic and classical ballets and in works of modern dance.

Page 6 - Composers and Choreographers

The music to which Roseman drew the Dance spans the centuries. Henry Purcell's suite Abdelazer, dating from 1695, was utilized by José Limon in 1949 for his ballet The Moor's Pavanne, based on Shakespeare's Othello (see "Biography,'' Page 2 - "World of Shakespeare''). Throughout the website are Roseman's drawings exemplifying a variety of styles of dance choreographed to an extensive range of music by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Adam, Wagner, Verdi, Delibes, Tchaikovsky, Massenet, Mahler, Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Hindemith, Thomson, Copland, and Duke Ellington (to mention a representative selection), as well as the ragtime rhythms of Joseph Lamb, the pulsating beat of synthesizer and percussion in a score by Thom Willems, and traditional spiritual and gospel music of Afro-American culture.

Composing Music for Romantic and Classical Ballet

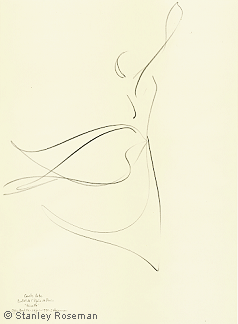

2. Carole Arbo, 1995

Paris Opéra Ballet

Giselle

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Paris Opéra Ballet

Giselle

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

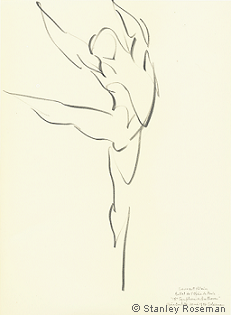

3. Fanny Gaïda, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

La Bayadère

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux

Paris Opéra Ballet

La Bayadère

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux

4. Marie-Claude Pietragalla, 1994

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Rite of Spring

Pencil on paper, 37.5 x 27.5 cm

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Paris Opéra Ballet

The Rite of Spring

Pencil on paper, 37.5 x 27.5 cm

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Music and Dance

8. Laurent Hilaire, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

Ninth Symphony of Beethoven

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Private collection, Maine

Paris Opéra Ballet

Ninth Symphony of Beethoven

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Private collection, Maine

7. Nicolas Le Riche, 1996

Paris Opéra Ballet

Ninth Symphony of Beethoven

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Private collection, Michigan

Paris Opéra Ballet

Ninth Symphony of Beethoven

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Private collection, Michigan

Romantic ballet in the nineteenth century produced such acclaimed ballet scores as Adolphe Adam's Giselle, choreographed by Jean Corelli and Jules Perrot; and Léo Delibes' Coppélia, choreographed by Arthur Saint-Léon. Both ballets had their world premieres at the Paris Opéra, in 1841 and 1870, respectively. In a text to accompany his drawings, Roseman writes: "The marvelous score for Giselle by Adolphe Adam employs an early use of leitmotifs in music to establish character and further the story.'' Bringing to a close the era of Romantic ballet was Coppélia by Léo Delibes. "His symphonic ballet score influenced a following generation of composers, including Tchaikovsky, who acknowledged his debt to the French composer.''[1]

In the last decade of the twentieth century, Paris Opéra Ballet Masters Eugene Polyakov and Patrice Bart remounted Giselle after the original choreography. At a performance in 1995, Roseman drew from the wings of the stage Carole Arbo as the tragic heroine who is summoned from the grave to dance in a moonlit forest with nocturnal spirits of other young maidens.

The great tradition of classical ballet developed in the second half of the nineteenth century and generated famous works that include Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, and The Nutcracker; Minkus' Don Quixote and La Bayadère; and Glazunov's Raymonda, all of which are represented in Roseman's drawings on the dance at the Paris Opéra.

Ballets Russes

The impresario Serge Diaghilev commissioned ballet scores for the Ballets Russes, which flourished between 1910 and 1929, when The Prodigal Son, with a score by Prokofiev, was given its world premiere in Paris, some three months before Diaghilev passed away. Productions in the early years of the Ballets Russes included L'Apres midi d'un Faune with the music of Debussy. Stravinsky composed two of his most celebrated works for the Ballets Russes: Petrouchka, the saga of a clown puppet with a soul; and The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du Printemps), which evokes tribal rituals in primitive Russia. The three ballets also had their world premiers in Paris: Petrouchka, 1911; L'Apres midi d'un Faune, 1912; and The Rite of Spring, 1913.

Energetic pencil strokes evoke a visual sensation of Stravinsky's pounding rhythms and capture the kinetic energy and emotion of the dancer in the terrifying climax of the ballet. The maiden leaps in a frenzy, legs bent under her tunic, arms flung forward, until exhausted, she collapses and dies.

Nicolas Le Riche is depicted advancing quickly forward, his right shoulder flexed as he stretches his arm out in front of him. The dancer's head is lowered; his left leg bent at the knee, with a curvilinear pencil stroke defining the taut, calf muscle. The thrust of the dancer's right leg propels him in pictorial space.

From Roseman's series of excellent drawings created at performances are presented here: Nicolas Le Riche and Laurent Hilaire, (figs. 7 and 8, below). With swift, vigorous strokes of the graphite pencil on paper, Roseman captures the dynamic dance movements of both star dancers.

The strong, diagonal composition emphasizes the expression of force and forward movement in this superb drawing of the male dancer.

Dancing to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, Laurent Hilaire takes a joyful leap in Roseman's drawing. The artist describes the dancer's high kick, raised arms, and inclined head and torso with calligraphic pencil lines charged with energy. The dancer's left leg, in the center of the composition, supports the leaping figure and divides equally the picture plane.

Roseman combines description and abstraction in this spirited image of the male dancer in performance at the Paris Opéra.

1. John Warrack, Tchaikovsky, (London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd, 1989). p. 92, 93.

2. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris - Drawings on the Dance at the Paris Opéra

(text in French and English), (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996), p. 12.

3. Alexandre Benois, Reminiscences of the Russian Ballet, (London: Putnam, 1941), p. 326.

4. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris - Drawings on the Dance at the Paris Opéra,

(Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996), p. 12.

5. IXe Symphonie de Beethoven, Choreography by Maurice Béjart, (Paris: L'Opéra de Paris, 1996), p. 11.

2. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris - Drawings on the Dance at the Paris Opéra

(text in French and English), (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996), p. 12.

3. Alexandre Benois, Reminiscences of the Russian Ballet, (London: Putnam, 1941), p. 326.

4. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris - Drawings on the Dance at the Paris Opéra,

(Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996), p. 12.

5. IXe Symphonie de Beethoven, Choreography by Maurice Béjart, (Paris: L'Opéra de Paris, 1996), p. 11.

Please note that the website has been republished for Internet Explorer 11.

At the Paris Opéra in the spring of 1996, Roseman drew the Paris Opéra Ballet in Maurice Béjart's Ninth Symphony of Beethoven, choreographed to the composer's Ninth Symphony, a celebrated composition for orchestra and chorus. The Paris Opéra program states: 'Several of Ludwig van Beethoven's writings attest to the fact that he had thought of dance while composing his last symphony (finished in 1824). Preliminary outlines for the Finale prescribe voices to sing Schiller's poem Ode to Joy and bear the mention 'mit Chor und Tanz' ('with Chorus and Dance').'[5]

Throughout the website are presented Roseman's drawings created at performances of modern dance that resulted from collaborations between composers and choreographers. From the Martha Graham Dance Company's guest appearance at the Paris Opéra in 1991 is the beautiful drawing, (fig. 10, below), of Joyce Herring in El Penitente.

Joyce Herring, principle dancer of the Graham Company, admirably portrayed the three-fold personage of the Virgin, Mary Magdalene, and the Mother. In the present work, rendered with a continuous flow of line and a compelling mise en page, Roseman expresses the contained movement and intensity of the dancer, wrapped in a long cape, her face in profile, her body bent forward as she is seen advancing across the picture plane.

10. Joyce Herring, 1991

Martha Graham Dance Company

El Penitente

Pencil on paper, 37.5 x 27.5 cm

Private collection, France

Martha Graham Dance Company

El Penitente

Pencil on paper, 37.5 x 27.5 cm

Private collection, France

Martha Graham choreographed the work to an evocative score composed by Louis Horst, who was the Musical Director for the Company and a leading musical figure in modern dance. The American composer and choreographer began their close association when Horst accompanied Graham in her solo debut in New York City in 1926. El Penitente premiered in 1940 and remains a standard work in the Graham repertory.

This page will present a further selection of drawings: Hervé Dirmann as the Merchant in Les Mirages, music by Henri Sauguet and choreography by Serge Lifar; Lionel Delanoë as the Wolf in Le Loup, music by Henri Dutilleux and choreography by Roland Petit; and Kader Belarbi as Petrouchka and Laure Muret as Columbine in Petrouchka, music by Igor Stravinsky and choreography by Michel Fokine.

From the invited companies making guest appearances at the Paris Opéra are drawings of Danilo Radojevic in American Ballet Theatre's production of Drink to me only with Thine Eyes, music by Virgil Thomson and choreography by Mark Morris; and the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater's The River, choreographed by Alvin Ailey to a score by Duke Ellington.

Please return again.

Please return again.

La Bayadère was Rudolf Nureyev's last ballet. Nureyev derived his choreography from the classical ballet La Bayadère choreographed by Marius Petipa for the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg in 1877. Nureyev's version premiered at the Paris Opéra in 1992 and has become a standard work in the Company's repertory. To the evocative score by Ludwig Minkus, Paris Opéra audiences are transported to a past century in India, where is revealed the fateful love story of Nikiya, a temple dancer, or bayadère; and Solor, a noble Indian warrior.

The Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux conserves the beautiful drawing of Fanny Gaïda as Nikiya, presented here, (fig. 3). With fluent, curvilinear strokes of a graphite pencil, Roseman renders the star dancer executing a graceful arabesque.

Roseman writes of his drawings on the dance: ''I sought to express not only a dancer's movements that led up to and completed the grand steps and gestures but also intermediate and complementary dance movements that for me spoke personally of the individual dancer.''

Roseman drew dancers in ballets and works of modern dance choreographed to symphonies and concertos; music from operas, notably those by Gluck, Rossini, Wagner, Verdi, Bizet, and Massenet; and orchestral works, such as Debussy's Prélude à l'Après-midi d'un Faune and Ravel's Rhapsody for Violin and Orchestra. Compositions for solo instrument include piano pieces by Mozart, Chopin, Schönberg, as well as Virgil Thomson's Etudes. Paris Opéra Ballet Master Eugene Polyakov choreographed the pas de deux Comme on respire to John Field's Nocturne no.4 in A Major for piano. Jacques Garnier choreographed Aunis for three male dancers to the contemporary accordion music of Maurice Pacher; and Jerome Robbins set A Suite of Dances to Bach's Suites for Solo Cello.

© Stanley Roseman

El Penitente is set in the American southwest where a troupe of traveling players of a religious sect enact rituals of penitence and purification.

Rudolf Nureyev choreographed his first production of Romeo and Juliet, with the symphonic score by Prokofiev, for the London Festival Ballet in 1977. The English prima ballerina Patricia Ruanne danced Juliet to Nureyev's Romeo. When Nureyev was appointed Director of the Dance at the Paris Opéra in 1983, he invited Ruanne to be his assistant in overseeing rehearsals and performances.

In the present work, Roseman transposes with an economy of line the dance movement onto the surface of the paper. Silvery strokes of the graphite pencil accent the raised shoulders and the graceful ''S'' curve of the danseuse's neck as she lowers her head to the side. A heartfelt emotion is expressed in this eloquent work of art.

The opening scene of Petrouchka takes place in the Square of the Winter Palace, in St. Petersburg, where puppet shows were traditional entertainment at the Shrovetide Fair, which preceded Lent. An old conjuror brings to life three puppet characters: the clown Petrouchka and his rival the Moor, both of whom are in love with a pretty but fickle danseuse Columbine.

At the opening night performance, on 9 February 1994, Roseman created the splendid drawing presented here, (fig. 5), of star dancer Charles Jude as Petrouchka. With an economy of line, the artist defines the puppet's form and the shape of his costume and floppy hat. His arms are down at his side and crossed in a characteristic gesture. A continuous pencil line renders the turn of Petrouchka's head and neck and the clown puppet's ruff.

The drawing expresses the sympathetic character of Petrouchka, his vulnerability and naiveté. The artist has emphasized the feeling of movement by the contrapposto position of Petrouchka's body turning to the left as his head turns towards the viewer's right and the expanse of pictorial space. In Roseman's absorption in the creative process and delineation of the figure, a treble clef appears in the flowing lines, as if the dancer were embracing the music in his arms.

5. Charles Jude, 1994

Paris Opéra Ballet

Petrouchka

Pencil on paper, 37.5 x 27.5 cm

Collection of the artist

Paris Opéra Ballet

Petrouchka

Pencil on paper, 37.5 x 27.5 cm

Collection of the artist

"Stanley Roseman's drawings show the many facets of his great talents as a draughtsman."[4]

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France

"The drawings that you so thoughtfully brought to us are superb.

I love immensely the drawings of the dancers,

which have an astonishing spontaneity of action and of refinement....

Please convey my congratulations to Monsieur Stanley Roseman for the great quality of his drawings.

We are proud to incorporate the work in our collection."

I love immensely the drawings of the dancers,

which have an astonishing spontaneity of action and of refinement....

Please convey my congratulations to Monsieur Stanley Roseman for the great quality of his drawings.

We are proud to incorporate the work in our collection."

- Barbara Brejon de Lavergnée

Curator of the Cabinet of Prints and Drawings

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

Curator of the Cabinet of Prints and Drawings

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

6. Patricia Ruanne, 1995

Paris Opéra Ballet

Romeo and Juliet

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

Paris Opéra Ballet

Romeo and Juliet

Pencil on paper, 38 x 28 cm

Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille

Patricia Ruanne was later promoted to Ballet Master of the Paris Opéra. After Nureyev retired from the company's directorship in 1989, Ruanne had responsibility for remounting Nureyev's ballets. Thus a wonderful series of events enabled Roseman to draw Nureyev's first Juliet in his own choreography as Ruanne danced passages of the ballet in her demonstrations at rehearsals and relived her great role as Shakespeare's tragic heroine.

The Paris Opéra Ballet has remounted and maintained in its repertory productions of the Ballets Russes. Roseman drew at a number of those ballets, including the four mentioned above. The drawing presented here, (fig. 4), is of star dancer Marie-Claude Pietragalla in The Rite of Spring, choreographed by Vaslav Niijinsky. This dynamic drawing depicts the dancer as "the Chosen One,'' the tribe's sacrificial maiden.

Roseman created a series of impressive drawings from the Paris Opéra Ballet's remounting of Petrouchka, choreographed by Michel Fokine to the renowned score by Stravinsky. The co-founder and artistic director of the Ballets Russes was Alexandre Benois, scenarist of the poignant story of the Russian clown puppet Petrouchka, "the personification of the spiritual and suffering side of humanity,'' to quote from Benois' autobiography Reminiscences of the Russian Balllet.[3]

This celebrated ballet which premiered in 1940 in the United States has a Western theme with dancers in cowboy hats and boots and dance sequences that include tap dancing and a traditional American square dance. The San Francisco Ballet made its first guest appearance at the Paris Opéra in July 1994 and presented Rodeo to Parisian audiences.

In the impressive drawing Male Dancer, (fig. 9), a single, curvilinear stroke of the pencil delineates the dancer's neck, head, and cowboy hat. Vigorous lines describe the cowboy's raised shoulders, his left leg lifted and bent at the knee, and his right leg, a pillar of support. A master draughtsman, Roseman renders with an economy of line the exuberance of the male dancer in Rodeo.

9. Male Dancer, 1994

San Francisco Ballet, Rodeo

Pencil on paper, 37.5 x 27.5 cm

Collection of the artist

San Francisco Ballet, Rodeo

Pencil on paper, 37.5 x 27.5 cm

Collection of the artist

Dance companies from the Unites States receive warm and enthusiastic welcomes from Parisian audiences. "As an American artist in Paris,'' Roseman recounts, "I was very happy to include in my drawings on the dance at the Paris Opéra the American ballet Rodeo by the distinguished American choreographer Agnes de Mille to a rousing score by the eminent American composer Aaron Copland."

Collaboration between Composers and Choreographers

The beautiful and poignant drawing of Patricia Ruanne as Juliet (fig. 6) is conserved in the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille. The Museum houses a renowned collection of Master Drawings, notably from the Italian Renaissance, including an outstanding group of drawings by Raphael as well as drawings from the French, Flemish, German, and Dutch schools.

Acquiring a suite of Roseman's drawings for the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, Barbara Brejon de Lavergnée, distinguished Curator of Prints and Drawings, writes in a cordial letter, dated 13 May 1996, to Ronald Davis:

Francis Ribemont, Chief Curator of Patrimony of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux, writes in a cordial letter to Roseman to acknowledge the Museum's acquisition of three drawings from the artist's work from Paris: the clown Kassya in a production from the Ranelagh Theatre and drawings of star dancers Fanny Gaïda and Elisabeth Maurin at the Paris Opéra.

"The Musée des Beaux-Arts of Bordeaux is very honored by the donation of three of your drawings:

Kassya, 1995, Fanny Gaïda, 1996, and Elisabeth Maurin, 1995,

that you have generously offered. They enrich the collection of 20th century drawings

that are conserved in the museum and constitute with the series of the Monks

and The Balcony by Jean Genet an ensemble of very great interest.''

Kassya, 1995, Fanny Gaïda, 1996, and Elisabeth Maurin, 1995,

that you have generously offered. They enrich the collection of 20th century drawings

that are conserved in the museum and constitute with the series of the Monks

and The Balcony by Jean Genet an ensemble of very great interest.''

- Francis Ribemont

Chief Curator of Patrimony

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux

Chief Curator of Patrimony

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux

The excellent mise en page contributes to the feeling of movement of the danseuse in pictorial space. Her right arm raised high complements her outstretched left arm and her head gently inclined.

The artist conveys the femininity and lyricism of Fanny Gaïda in her emotive portrayal of the lovely temple dancer Nikiya.

The artist has depicted with fluent pencil lines the ethereal femininity of the star dancer as Giselle. This fine drawing Carole Arbo, (fig. 2), is conserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which states in its exhibition publication that Roseman's drawings "translate and transmit the dancer's movements in a single, pictorial image."[2]