The MONASTIC LIFE

''No one, I believe, in 1,500 years of Christian monachism has catalogued, defined

and described so clearly or so beautifully the business of the monastic life.

No writer, no sculptor, no painter, no architect has refined a distillation so pure,

so accurate, so breathtakingly clear as Roseman has done.''

and described so clearly or so beautifully the business of the monastic life.

No writer, no sculptor, no painter, no architect has refined a distillation so pure,

so accurate, so breathtakingly clear as Roseman has done.''

- The Times, London

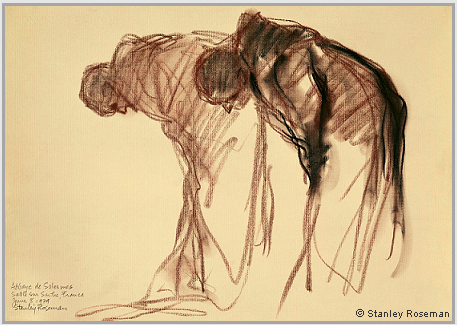

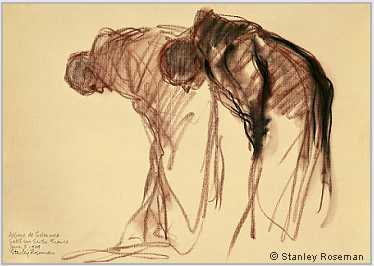

Two Monks Bowing, 1979

Abbaye de Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Abbaye de Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

When Roseman began his work in the monasteries in the late 1970's, monastic life was little known to the general public and an unfamiliar subject for a modern artist's work. Monastic life was rarely a topic for coverage in the popular press. Unlike today, monasteries then were closed to television cameras and documentary filmmakers, and the Internet, with its vast information resources, did not exist. Roseman's paintings and drawings brought a new awareness of the centuries-old and far-reaching contemplative tradition in Western culture.

The respected art journal ARA arte religioso actual, Madrid, published in the fall of 1979 an enthusiastic reportage entitled ''Stanley Roseman y la Vida Monastica'' and states: ''The pictures - splendid and telling all at once - form the stimulating vanguard towards so original and deep a study of the monastic life.''

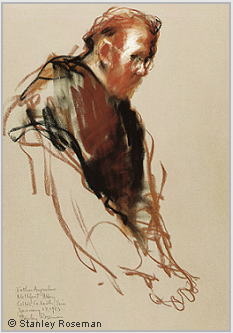

2. Father Augustine in Choir, 1983

Trappist Abbey of Mellifont, Ireland

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Dallas Museum of Art

Trappist Abbey of Mellifont, Ireland

Chalks on paper, 50 x 35 cm

Dallas Museum of Art

3. Dom Henry,

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm.

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978

St. Augustine's Abbey, England

Oil on canvas, 50 x 50 cm.

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen

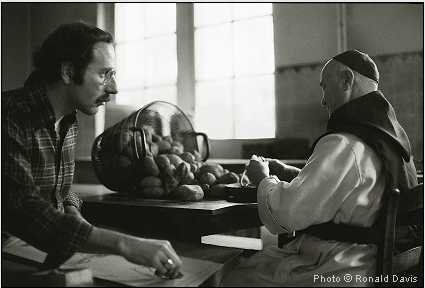

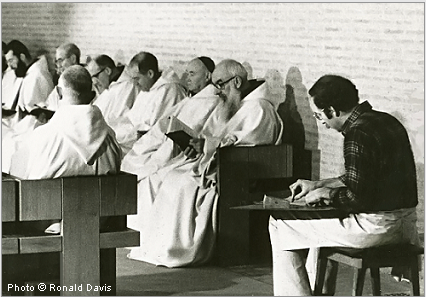

4. Roseman drawing a Belgian Trappist monk in the kitchen, 1981.

Daily Life in the Monastery

8. Two Monks Bowing in Prayer, 1979

Abbaye de Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Abbaye de Solesmes, France

Chalks on paper, 35 x 50 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Drawings from the Monasteries

Albertina, Vienna

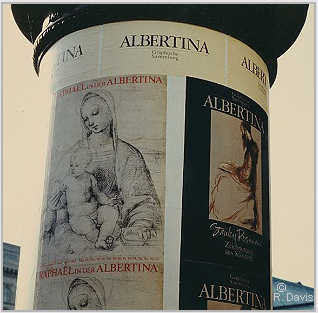

9. and 10. At the entrance to the Albertina,

the column displaying the posters announcing the museum's exhibitions:

Raphael in der Albertina and

Stanley Roseman - Zeichnungen aus Klöstern, 1983

the column displaying the posters announcing the museum's exhibitions:

Raphael in der Albertina and

Stanley Roseman - Zeichnungen aus Klöstern, 1983

The Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, presented in 1983 the first one-man exhibition of drawings by an American artist: Stanley Roseman-Zeichnungen aus Klöstern (Drawings from the Monasteries). Roseman, then thirty-eight years old, was further honored by the Albertina opening the exhibition of his drawings on September 6th concurrently with the opening of the exhibition of the museum's Raphael drawings on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the Renaissance master's birth. The exhibition of Roseman's drawings at the world-renowned Albertina brought great prestige to the artist and his work.

Over the years, Roseman continued to resume his work on the monastic life with cordial invitations from monasteries he had not been to before as well as returning to those he knew well. The monks' and nuns' high esteem for the artist's paintings and drawings, expressed in conversation and in correspondence; their admiration for his knowledge of monastic history; and their appreciation of his own contemplative nature earned Roseman enduring friendships and repeated invitations to take up again his work in their monasteries.

© Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis - All Rights Reserved

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

Visual imagery and website content may not be reproduced in any form whatsoever.

An Invitation from the Abbot Primate in Rome

The Abbot Primate of the Order of St. Benedict, Dom Victor Dammertz, OSB, invited Roseman and Davis as his guests at the abbot's residence, the Badia Primaziale Sant'Anselmo, in Rome, in winter of 1979. The Abbot Primate was greatly encouraging to Roseman for his work. In letter to the Vatican, the Abbot Primate writes:

''This is, as far as I know, the first time any artist of note has undertaken such a project. Roseman's work has greatly impressed those of us in the monastic world

who have been fortunate enough to see it. His pictures are technically of the highest quality,

and he has succeeded in a remarkable way in conveying the spiritual dimension of his subject.''

who have been fortunate enough to see it. His pictures are technically of the highest quality,

and he has succeeded in a remarkable way in conveying the spiritual dimension of his subject.''

- Dom Victor Dammertz, OSB

Abbot Primate of the Order of St. Benedict

Abbot Primate of the Order of St. Benedict

"You have delivered to me two drawings by Stanley Roseman, which I have acquired for the Albertina. I thank you and want to express my conviction that the artist is an outstanding draughtsman and painter to whom much recognition and success are due."

- Walter Koschatzky

Director of the Albertina

Director of the Albertina

STANLEY ROSEMAN

Having a love of books, Roseman often sought the ambiance of monastery libraries in which to draw as well as a place for his own reading and study. He knew well the library at St. Adelbert from his first sojourn at the monastery in 1978, when Brother Thijs, the librarian, assisted the artist in his early research on monasticism.

Roseman was invited to join monastic communities in choir when the monks or nuns assembled for the Divine Office, the daily round of communal prayer that is central to the monastic life. In his text the artist writes of the Judeo-Christian tradition of psalmody in monastic observance.

The artist drew monastic communities taking meals in silence in the refectory. He drew individuals studying in the library, reading and writing at their desks in the scriptorium, and having coffee or tea in the calefactory.

Roseman drew monks and nuns in prayer and meditation and in various kinds of work and humble chores, such as peeling potatoes in the kitchen.

The Albertina was the first museum to acquire Roseman's drawings from the monasteries. In November of 1978 Ronald Davis was invited by Dr. Walter Koschatzky, Director of the Albertina, to show him a selection of Roseman's drawings. Dr. Koschatzky purchased two drawings made in Flemish Trappist monasteries the previous month. At their cordial meeting, the eminent Director of the Albertina thoughtfully wrote Davis a hand-written letter acknowledging the acquisition of the drawings and praising the artist for his work:

"Nevertheless, in Western Art monastic life accounts for a small percentage of the extensive imagery on religious subject matter. From the thirteenth century there grew a popular demand for pictures of saints of the newly founded mendicant orders, which include the Order of Friars Minor, or Franciscans; Order of Friars Preachers, or Dominicans; Order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, or Carmelites; and the Austin Friars. Franciscan and Dominican friars were especially common to the cityscape and actively sought contact with society in contrast to those who sought the contemplative life behind the monastery walls.''

You are also cordially invited to visit: www.stanleyroseman-monasticlife.com

"a sweeping artistic project"

''When I began researching and planning my work on the monastic life, my thoughts were towards Europe for monastic life is interwoven with the history and culture of Europe. . . .[1]

The President of France, Jacques Chirac, writes in a cordial letter, dated 9 May 1995, to Roseman in praise of the artist's work:

Stanley Roseman embarked in 1978 on what the Los Angeles Times calls ''a sweeping artistic project.'' The artist was invited to live in Benedictine, Cistercian, Trappist, and Carthusian monasteries and share the day-to-day life in the cloister. Behind the monastery walls, Roseman painted portraits and drew monks and nuns of the four monastic orders of the Western Church and created a monumental and critically acclaimed work on the monastic life - a life centered on contemplation and prayer in observing the Prophet's call to prayer in the Book of Psalms.

Roseman's ecumenical work, brought to realization in the enlightenment of Vatican II, depicts monks and nuns of the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran faiths. Roseman created his work in over sixty monasteries throughout England, Ireland, and Continental Europe. The artist writes in a text to accompany his work:

"With the expansion of Benedictine monasticism throughout Europe in the Carolingian Age and Cistercian monasticism in the Twelfth Century Renaissance, the monastic orders - adhering to the precept ora et labora, "prayer and work" - continued to encourage spiritual ideals and contributed greatly to the cultural and economic advancement of Western civilization. . . .

An Unprecedented Work on the Monastic Life

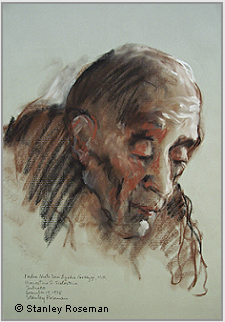

Dom Henry, Portrait of a Benedictine Monk, 1978, (fig. 3), was painted at the outset of Roseman's sojourns in the monasteries. The magnificent painting was acquired in 1986 by the Chief Curator of the Museums of France, François Bergot, for the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, of which he was the Director. In a cordial letter to Roseman, the Chief Curator of the Museums of France expresses, "my admiration for this work of art of profound insight and spirituality."

The rapport between the artist and the monk is evident in Roseman's portrait of Dom Henry, who was in his early seventies when he kindly sat for the artist at St. Augustine's Abbey on the coast of Kent.[3]

"By the late sixth century, monasteries were flourishing in Gaul, on the Italian peninsula, and in the British Isles. Irish monks brought the ascetic practices and scholarly pursuits of Celtic monasticism to the Continent as other contemplatives ventured northward from Italy and crossed the English Channel. . . . Many monasteries in the Middle Ages were intellectual centers of renown.[2] . . ."

Page 6 - The Monastic Life

Biography: Page 6

Roseman, who is of the Jewish faith, made the journey to the monasteries with his colleague Ronald Davis, of the Roman Catholic faith. Davis wrote letters to monasteries to relate Roseman's interest in monastic life as a subject for his paintings and drawings. Davis helped in the research and took on the responsibilities for organizing their travels. The first letter they received from a monastery was an enthusiastic response from Abbot Gilbert Jones of St. Augustine's Abbey.

The Abbot writes that Roseman's prospective work on the monastic life "sounds most exciting and of course you may start off here. . . .'' Abbot Gilbert thoughtfully mentions that he could suggest other monasteries and encourages them to go to Subiaco, where "St. Benedict began his search for God - a glorious place and full of a very special character.'' Abbot Gilbert was reassuring that between St. Augustine's and Subiaco "there are many possibilities for a fascinating pilgrimage,'' and concludes: "Let me know when to expect you.''

The Abbot and the Community were warmly welcoming that April 1978 and offered gracious hospitality. Roseman and Davis were given rooms in the monks' dormitory, took their meals with the monks in the refectory, and shared in the daily life in the monastery. With great enthusiasm Roseman began his work on the monastic life.

A major part of Roseman's work on the monastic life is expressed in the medium of drawing, considered the foundation of the visual arts. The celebrated, sixteenth-century Florentine architect, painter, and author Giorgio Vasari writes that drawing (disegno) is ''the parent of our three arts, Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting, having its origin in the intellect.''[4]

''The Prophet states in the Book of Psalms, 'At midnight I rise to praise you,' and 'Seven times a day I praise you.' This call to prayer from Psalm 119, 'In praise of the divine Law,' gives monastic life its definitive form and structure.[5]

5. Roseman drawing Trappist monks in choir

St. Sixtus Abbey, Belgium, 1981.

St. Sixtus Abbey, Belgium, 1981.

Davis' photographs complement Roseman's drawings and paintings on the monastic life and provide a visual record of the artist at work behind the monastery walls.

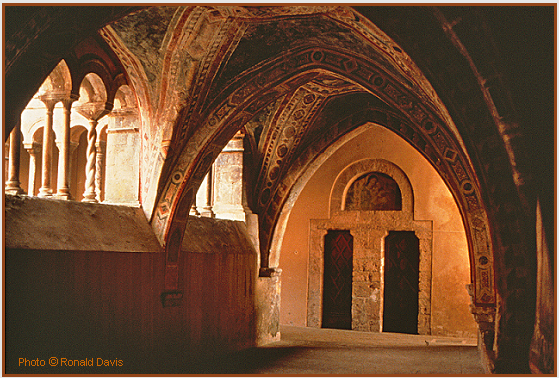

At the Abbey of Subiaco, Italy

"The canonical hours, called the Divine Office, are founded on singing the Psalms. 'Lord open my lips, and my mouth will proclaim your praise,' from Psalm 51, begins Vigils, the first and traditionally the longest Office, sung to keep watch in the night.[6] At dawn, the Psalms for Lauds offer renewal and hope; at day's end, the Psalms for Compline bless the Lord and ask God for protection in the dark."

"The monastery bell tolls the Night Office, or Vigils, and the daytime Offices of Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, and None, Vespers in the late afternoon, and Compline at the end of the day.

Roseman and Davis concluded their first year in monasteries at the Benedictine Abbey of Subiaco in December 1978. The cordial invitation was of great historic significance for the artist's work on the monastic life. The Abbey of Subiaco situated in a mountain valley in the Latium region of central Italy, was founded in the sixth century by Benedict of Nursia, (c.480-c.547), the saintly Italian abbot whose rule known as the Rule of St. Benedict is the basis for monastic observance in the Western Church.

6. The Thirteenth-Century Cloister of the Abbey of Subiaco, Italy.

"Stanley Roseman lived in monasteries of monks and nuns of the four contemplative orders

throughout Europe and created an extensive oeuvre of chalk drawings

profoundly expressive of the individual and the interior life.''[7]

throughout Europe and created an extensive oeuvre of chalk drawings

profoundly expressive of the individual and the interior life.''[7]

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France

"Abbot Egidio welcomed me with kind words, a friendly smile, and a gentle hand on my shoulder as he brought me into his room. He thoughtfully placed a chair for me to sit by his side. The Abbot's gracious reception and the rapport he established communicated his warm feelings towards me and his encouragement of my work on the monastic life.

"The Abbot opened his breviary and read and prayed in silence, and I took up my paper and chalks and began drawing. . . ."

The artist draws with a painterly use of the chalk medium on gray paper. With a chiaroscuro modeling of light and shade, Roseman has beautifully rendered the face of Don Egidio and conveys a spiritual intensity in this deeply felt portrait of the Abbot of Subiaco.

"Sharing a private time with the Abbot of Subiaco and his giving me the opportunity to draw him in the intimacy of his cell was for me an enriching experience. I am deeply grateful to him, for drawing Abbot Egidio Gavazzi gives my oeuvre on the monastic life a spiritual lineage directly back to St. Benedict, the first Abbot of Subiaco and the Father of Western monasticism.''

7. Abbot Egidio Gavazzi, 1978

Abbey of Subiaco, Italy

Chalks on paper, 48 x 33 cm

Private collection

Abbey of Subiaco, Italy

Chalks on paper, 48 x 33 cm

Private collection

At Subicao, Roseman was invited to draw Abbot Emeritus Don Egidio Gavazzi, (fig. 7, below). The Abbot, from a prominent family in Lombardy, had been an engineer whose calling to the monastic life brought him to Subiaco. He became Coadjutor Abbot in 1951 and Abbot the following year. He was a Councillor Father at the Second Vatican Council, and with first-hand knowledge he guided the community of Benedictine monks at Subiaco during the historic changes resulting from Vatican II. Abbot Egidio retired in 1974 at the age of 70, revered as a holy man.

Roseman speaks of drawing the ascetic, abbot emeritus in his cell: "Cenobitic monasticism refers to religious living in community; therefore, a monk's cell is his retreat, a place where - as the etymology of the word 'monk' suggests - a monk can be 'alone' or 'apart from.' I felt honored by the invitation from Abbot Egidio to draw him in his cell.

The Times, London, published in 1980 a superlative, full-page review on Roseman's work. (See the quote at the top of this page.) The review features the artist's deeply felt portrait of Don Egidio Gavazzi, Abbot of Subiaco.

The Times review features at the top of the page the magnificent drawing Two Monks Bowing in Prayer, Abbey of Solesmes, 1979, (fig. 8) in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Solesmes is renowned for the study and preservation of Gregorian chant. The reverential musical expression developed mainly within the context of monastic life, with the golden age of composition of the chant dating from the fifth to eighth centuries.[8] Gregorian chant has its origins in the singing of the Psalms in ancient Jewish liturgical worship in the Temple and the Synagogue.[9] Psalmody, the singing or chanting of the Psalms, is the foundation of the Divine Office.

Roseman drew this spiritual work of art at the Divine Office in the French Benedictine Abbey in June of the second year of his work in monasteries.

The Director of the National Gallery of Art, J. Carter Brown, cordially writes to Roseman on May 7, 1981, to say that the Museum's Board of Trustees at their meeting that day "gratefully accepted" the artist's "generous offer" to make a gift of his drawing from the Abbey of Solesmes in loving memory of his father, Bernard Roseman. The eminent Director concludes his letter of appreciation to the artist:

"May I add my own warmest personal thanks for your interest in the Graphic Arts Department of the Gallery and say how very pleased we all are to acquire this fine example of your drawings."

- J. Carter Brown, Director

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

" 'Two Monks Bowing,' magnificent example of a work very successfully realized

that you have dedicated to the contemplative life.

I have greatly appreciated the classical tradition of your draughtsmanship,

the magnificently suggested volumes, the precision of the forms and the proportions.

that you have dedicated to the contemplative life.

I have greatly appreciated the classical tradition of your draughtsmanship,

the magnificently suggested volumes, the precision of the forms and the proportions.

With my congratulations.''

- Jacques Chirac

President of France

- Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro

''The project is a splendid artistic collection, an historic record of a way of life

never seen before on such a scale. . . . Each drawing is a gem of the first quality

and all of them together offer a unique impression of monastic life.''

never seen before on such a scale. . . . Each drawing is a gem of the first quality

and all of them together offer a unique impression of monastic life.''

The eminent Abbot of Solesmes, Dom Jean Prou, writes in his gracious letter, dated July 7th 1980, to Stanley Roseman and Ronald Davis:

"Thank you for having sent me a copy of the article from 'The Times' that relates your monastic and artistic tour; I see there that Solesmes has a good place. Be assured that you also have a good place in my prayers, and I often ask God to shower you with His favors.

+ Fr. Jean Prou

Abbot of Solesmes

Abbot of Solesmes

"Please know, dear friends, of my sincere remembrances in the Lord."

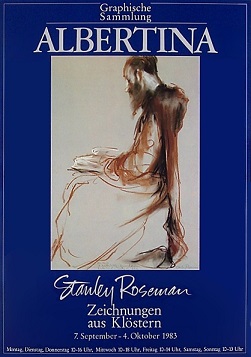

11. Albertina exhibition poster:

Stanley Roseman

Zeichnungen aus Klöstern, 1983

Stanley Roseman

Zeichnungen aus Klöstern, 1983

From the sixth to twelfth century, monasteries were major producers of books on religious and secular subjects. Scholarship and literary work became an important part of Benedictine monasticism from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance; the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as with the Congregations of Saint Vanne and Saint Maur [10]; and to the present day.

Brother Thijs in the Library is rendered with a harmonious interplay of line and tone. In the gray light of the abbey library, Roseman drew the Benedictine monk, seen here in profile, absorbed in reading. Brother Thijs' ivory complexion is complemented by his dark hair and long beard, giving the monk an appearance consistent with his erudition as a Biblical scholar.

The Albertina exhibition presented a selection of Roseman's drawings representative of the two forms of monastic observance in the Western Church: the cenobitic, or communal life, followed by Benedictines, Cistercians, and Trappists; and the eremitic, or solitary life, followed by Carthusians. The artist's drawings in the exhibition were created in monasteries in England, Ireland, and on the Continent from 1978 to 1983.

1. The quoted excerpts are from a text Roseman has written on monastic life and his work in monasteries to accompany his paintings and drawings.

The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green read a draft of Roseman's manuscript and wrote in a gracious letter to the artist:

"You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. Charles Homer Haskins, The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1927), pp. 32, 33.

3. St. Augustine's Abbey, Ramsgate, is no longer a Benedictine Monastery. In 2010, the monastic community relocated to new premises in Surrey.

4. Giorgio Vasari, Vasari on Technique, (New York: Dover Publications, Inc.), p. 205.

5. The Psalter is comprised of one hundred and fifty Psalms. Psalms 10 to 148 in the Hebrew Bible are one number ahead of the Greek Septuagint

and Latin Vulgate Bibles. The Greek and the Vulgate combine Psalms 9 and 10 as well as Psalms 114 and 115 while separating into two parts

each Psalm 116 and Psalm 148. The Rule of St. Benedict uses the numbering of the Psalms in the Vulgate Bible.

6. Psalm 51 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 50 in the Vulgate.

7. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris (text in French and English), Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996, p. 10.

8. "Early Medieval Music,'' New Oxford History of Music, ed. Dom Anselm Hughes, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954), Vol. II, p. 101.

9. Ibid., pp. 1, 93, 94.

10. David Knowles, Great Historical Enterprises, (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd, 1962), pp. 35-62.

The Oxford scholar and Benedictine monk Dom Bernard Green read a draft of Roseman's manuscript and wrote in a gracious letter to the artist:

"You portray the background and the aims of life in monasteries so well, showing such a deep understanding of the monastic life.''

2. Charles Homer Haskins, The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1927), pp. 32, 33.

3. St. Augustine's Abbey, Ramsgate, is no longer a Benedictine Monastery. In 2010, the monastic community relocated to new premises in Surrey.

4. Giorgio Vasari, Vasari on Technique, (New York: Dover Publications, Inc.), p. 205.

5. The Psalter is comprised of one hundred and fifty Psalms. Psalms 10 to 148 in the Hebrew Bible are one number ahead of the Greek Septuagint

and Latin Vulgate Bibles. The Greek and the Vulgate combine Psalms 9 and 10 as well as Psalms 114 and 115 while separating into two parts

each Psalm 116 and Psalm 148. The Rule of St. Benedict uses the numbering of the Psalms in the Vulgate Bible.

6. Psalm 51 in the Hebrew Bible is numbered Psalm 50 in the Vulgate.

7. Stanley Roseman - Dessins sur la Danse à l'Opéra de Paris (text in French and English), Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1996, p. 10.

8. "Early Medieval Music,'' New Oxford History of Music, ed. Dom Anselm Hughes, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954), Vol. II, p. 101.

9. Ibid., pp. 1, 93, 94.

10. David Knowles, Great Historical Enterprises, (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd, 1962), pp. 35-62.

For the preparation of the exhibition Stanley Roseman - Zeichnungen aus Köstern, Davis worked closely with Dr. Koschatzky. The poster features the beautiful drawing from the Albertina's collection Brother Thijs in the Library, 1982, chalks on gray paper, St Adelbert Abbey, the Netherlands.

The Monastic Life continues on the following pages: Portraits from the Monastic World